Many of the peaks retain their snow caps, or are streaked with snow, until the early autumn, while in some of the recesses and gorges where it is partially screened from the sun’s rays, the snow never entirely disappears.

During the Meiji era, British mining engineer William Gowland—employed by the Osaka Mint—explored the Etchu and Hida regions. In his 1881 English guidebook, A Handbook for Travellers in Central & Northern Japan, he wrote of these landscapes:

The range bounding these provinces on the E. is the most considerable in the Empire, and might perhaps be termed the Japanese Alps.

A decade later, missionary and mountaineering enthusiast Walter Weston, while residing in the Swiss Alps, used Gowland’s guide to plan ascents of Yari-ga-take (槍ヶ岳), Hotaka-dake (穗高岳), and other peaks. However, when documenting his experiences, Weston took far less cautious than William Gowan. Declaring “Yari-ga-take, the Matterhorn of Japan; Chono-dake, a miniature Weisshorn” he boldly titled his 1896 account Mountaineering and Exploration in the Japanese Alps. Despite Weston’s book, most Japanese remained unaware of these “Alps” in their own backyard.

It fell to Japanese voices to awaken local interest. In 1894, geographer and critic Shiga Shigetaka published Theory of Japanese Landscapes (Nihon Fukeiron), urging readers to appreciate their alpine heritage. Inspired by this work, bank clerk Kojima Usui embarked on mountaineering expeditions, culminating in his 1902 conquest of Yari-ga-take’s summit. The following year, Usui and Weston met at the latter’s house in Yokohama, a historic encounter that led to the founding of the Japanese Alpine Club in 1905.

The snow-covered granite cliffs, the tender green birch forests, and the melting snow that formed trickling streams through the valleys. All that Usui saw in Kamikōchi became material for the association’s journal, telling the touching stories behind the difficult climbs up dangerous mountains. A few years later, his essays were compiled and reprinted as a handbook titled The Japanese Alps. With the Alps came the modern sport of mountain climbing to Japan.

In the following decade of ongoing debate, the definition of the Japanese Alps, originally referring to the Hida Mountains as seen by Gowland, was eventually expanded to include the Kiso and Akaishi ranges. The first generation of mountaineers reached a consensus on the Northern, Central, and Southern Alps.

As Easterners unfamiliar with the circumstances of the time, one might be somewhat sensitive to overly Westernized place names, even finding them a bit comical. Yet, compared to Hida, Kiso, and Akaishi, most Japanese perhaps preferred the term “Japanese Alps.” One reason could be that these Japanese mountain names are not necessarily older than “Japanese Alps.” In fact, the name “Kiso Mountains” was proposed by geologist Toyohisa Harada in the 1880s, while Hida and Akaishi were named even earlier by the German geologist Heinrich Edmund Naumann, whom the Meiji government commissioned to carry out geological surveys. It’s easy to imagine that, for ordinary mountaineering enthusiasts during the Meiji period, “Japanese Alps” was far more familiar than the academic “Hida,” “Kiso,” and “Akaishi.”

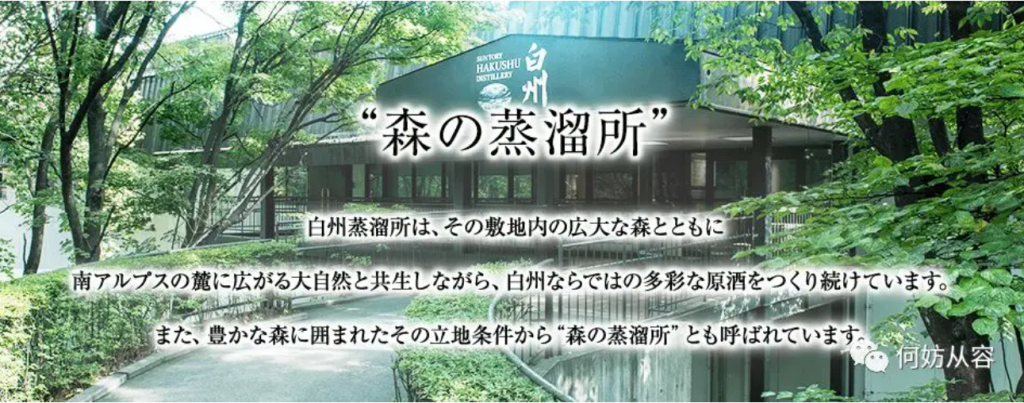

Whisky Distillery at the Foot of the Southern Alps

Booking a paid tour at Hakushu Distillery required a three-month advance reservation. From Shinjuku, it’s a two-hour JR ride to sip whisky deep in the forests bordering Yamanashi’s Southern Alps. For a well-trodden visitor route, though it’s billed as “in the forest,”the distillery really sits on the forest’s edge. There were no antelope, moon bears, deer, or fish in the streams; the wild charm lives only in books; and of course, no hidden dangers in the mountain quiet. A special “bird sanctuary” branches off the main road, leading on a ten-minute walk to a small pond. It was still hot in early September, and aside from a startled white stork, the pond’s edge was occupied only by me and countless mosquitoes.

The afternoon tour left time for lunch, so on a whim I wandered to a nearby soba shop overlooking a farm, facing the Yatsugatake range. The place had no fancy decor, just a clean, simple cafeteria. The menu had only three items: mori soba, juwari soba, and tempura. The tempura used local vegetables with a rice-starch batter. Though crisp, the batter hardened quickly once cool (most tempura shops avoid it), but luckily it was thin enough, and the farm fresh vegetables tasted great. Even a bit greasy, they were still delicious.

Honestly, the most peaceful, beautiful forest I saw was in Suntory’s promo video.

The tour steps are much the same at any whisky distillery, but Suntory’s is more convenient than Nikka’s, you can download their tour app ahead of time, and it even has a Chinese audio guide.

The process begins with milling malted barley and mixing it with heated brewing water. Enzymes convert starch into sugars during six hours of temperature-controlled mashing, producing clear wort with savory barley notes. While many distilleries now use stainless steel fermenters for precise temperature control, Hakushu East Plant retains massive wooden vats.

In those wooden casks, yeast ferments the sugars into alcohol and CO₂ over three days, making a wash of about 7% alcohol. Lactic acid bacteria on the wood and microbes from the Hakushu forest give the malt whisky its unique aroma. The fermenting room smelled of steamed buns; in northen China, people steam buns with rice wine mash, so I bet buns made with malt lees at Hakushu would be a real treat.

Distillation uses the different boiling points of alcohol and water to capture the fragrant oils and flavor compounds from fermentation. Like most distilleries, Hakushu distills twice. First distillation captures lighter flavors with alcohol vapors, producing 20% alcohol low wines. Second distillation refines richer components into 70% alcohol new make spirit. Hakushu uses direct fire stills: a straight still sends the wash directly to the condenser for a stronger, fuller spirit; a lantern shaped still lets vapors rise and condense repeatedly in the bulb, making a lighter, fresher spirit. Even the same shape but different size, or where the wash enters, gives each whisky its own character.

Whisky then slowly matures in large oak barrels. American white oak is most common because it’s stable and gives vanilla and wood notes. Clear, new spirit picks up wood character over time, developing mature aromas. In summer the wood expands, in winter it contracts. As it ages, natural evaporation called the “angel’s share”, reduces the barrel contents by about 2–3% per year.

Stepping into the warehouse made me dizzy, the air smelled so strong of whisky I felt drunk just breathing. Hakushu stores about 400,000 barrels of spirit across roughly 20 warehouses. Racks rise from floor to ceiling, and temperature, humidity, and barrel position all keep shaping the whisky’s final character.

After passing through a grand hall decorated with old stills, the paid tour ends with a tasting.

Four glasses, three flavors, the final Hakushu single malt was for making highballs.

The 12-year-old single malt from white oak is deeper and brighter in color than the others, with fruity and barley notes. It’s so smooth you might forget you’re even drinking something over 50% alcohol.

Having been struck by the heavy peat of Scotch, I found Hakushu’s light peat hardly peat, just fresh, a little smoky, a touch sweet.

The tasting offered three styles: neat, mizuwari (with water), and Highball. Like beginners praising a $10 wine, Hakushu’s single malt goes down too easy. It’s more suitable for a breezy ladies’ afternoon tea- pleasant, eager to please everyone. This is a carefully designed whisky- fresh and lively, yet too childish. It went down so easily that I finished it in just a few sips and missed the chance to try it with water…

I finally made a highball myself: fill a glass with ice, pour in whisky, add more ice, top with soda at a 1/3 or 1/4 ratio, stir gently; clap mint leaves between palms to release their scent and set them on top.

The Hakushu’s gift shop was utterly disppointing – no large bottles, and the 180 ml bundled with snacks. I skipped it and headed straight to the bar. That single malt was just ¥100 (under €1 per glass). So what more could you ask for? Childish or not, I was touched by their thoughtfulness. After this list, I never want to drink Japanese whisky in a local bar in China again!

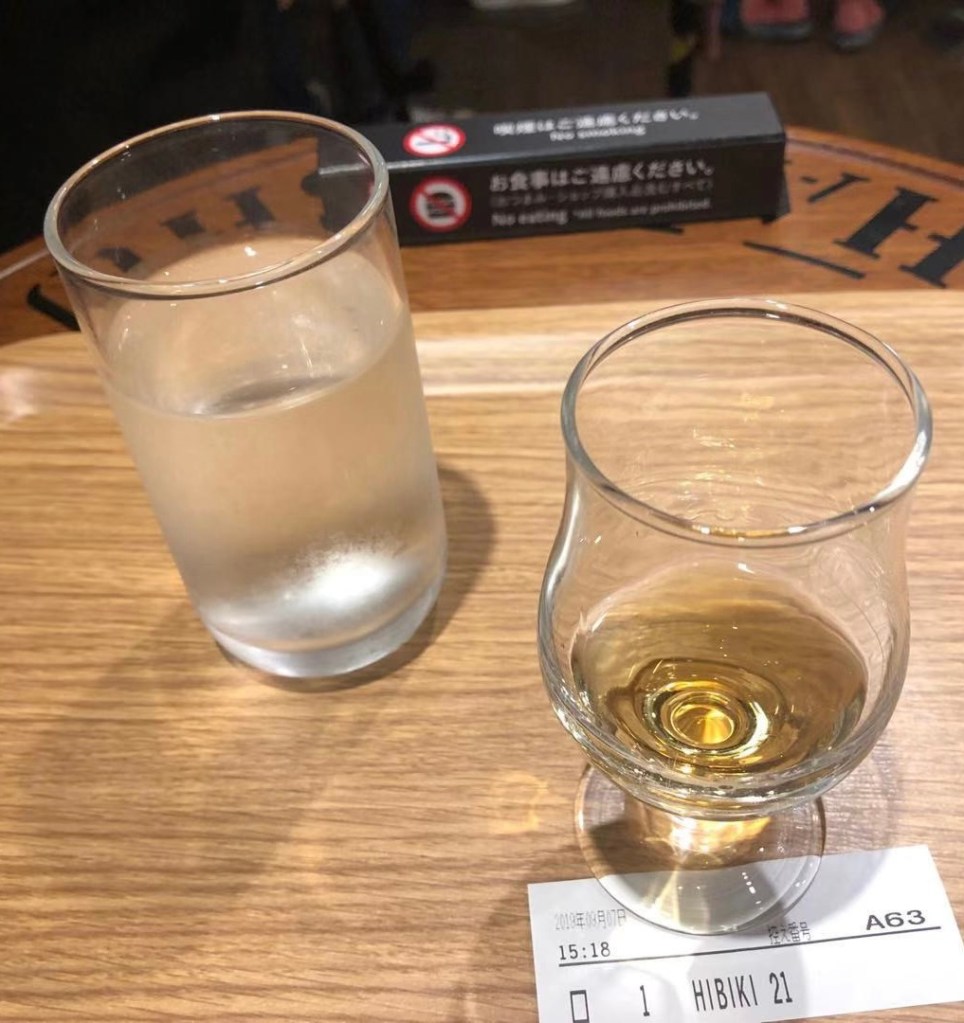

Saving my drink allowance for the priciest whisky, I didn’t hesitate to try a glass of Hibiki 30 Years, which retails one bottle for over €6,000-a. Uh… mildly underwhelmed by Japanese whisky—Hibiki 30 years’ complexity paled next to some Scotches, though it’s smooth and rich. A 30 year whisky should be that smooth, right?

While waiting for the bus, I tried a Hibiki 21 too—hard to describe; nine fewer years made it taste like a collapse… I’ll stick to Scotch.

Round trip from Tokyo to Hakushu, plus time wandering the distillery, the day was gone. Next time, I won’t book the tour, just bring jerky and friends to the bar; the four-hour trip won’t seem wasted. I suddenly wondered if the locals drop by once in a while for a drink, that would be nice and relaxing.

(This article was originally written six years ago. As I translated and rearranged it into English, I realized – it is really long. Thank you for taking the time to read all the way to the end.)

Leave a comment